Nuremberg (2025) is not a film that seeks comfort, closure, or easy moral triumph. Instead, it confronts the audience with the raw, uneasy aftermath of atrocity, placing justice itself on trial. Set in the fragile silence following World War II, the film transforms the courtroom into a battleground where law, conscience, and history collide under the weight of unimaginable crimes.

From its opening moments, Nuremberg establishes a tone of intellectual rigor and emotional restraint. There is no spectacle in suffering here—only the oppressive gravity of truth being dragged into the light. The film understands that the horror has already occurred; what remains is the far more difficult task of accountability.

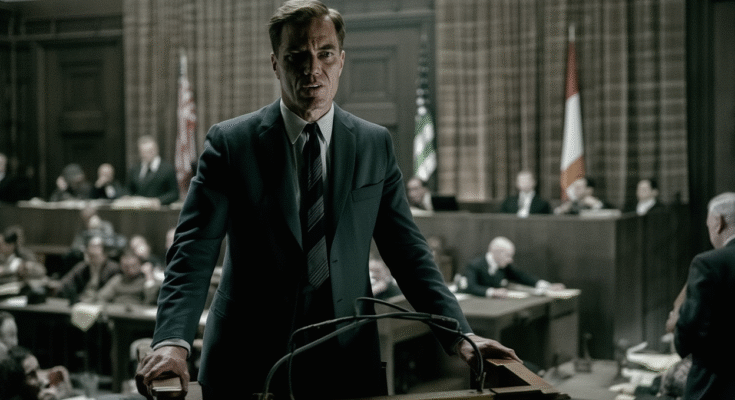

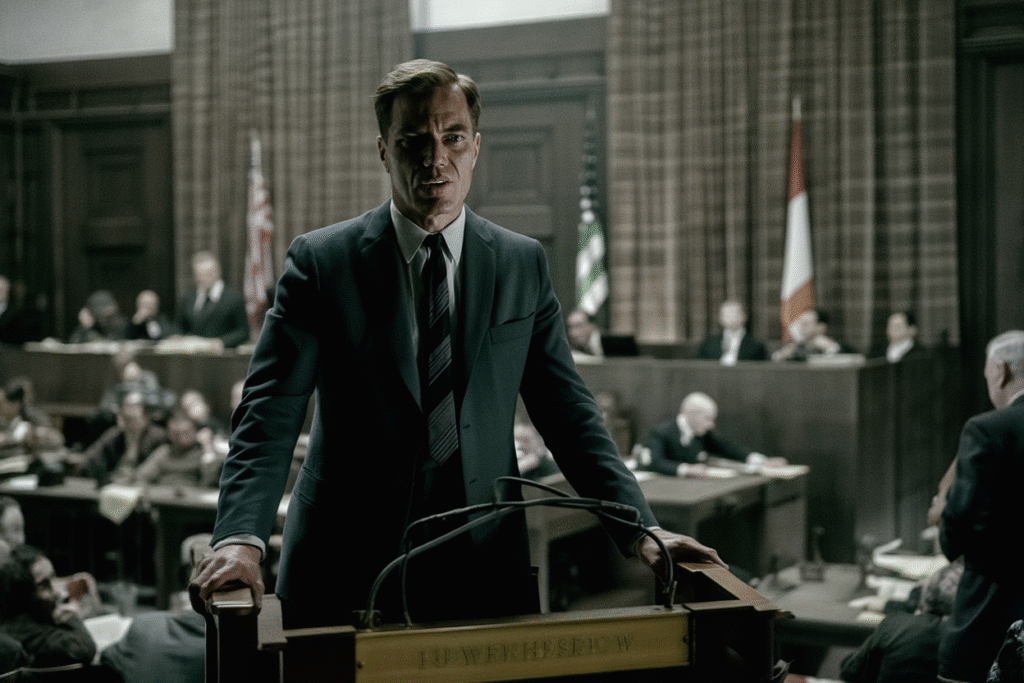

Michael Shannon delivers a performance defined by controlled intensity. His prosecutor is not fueled by vengeance, but by an almost painful commitment to principle. Every word feels measured, every argument burdened by the awareness that justice must be pursued without becoming indistinguishable from revenge.

Russell Crowe brings formidable presence and moral ambiguity to the proceedings. His performance embodies the tension between legal procedure and political reality, reminding us that even the pursuit of justice can be compromised by power, image, and national interest. Crowe plays this conflict with quiet authority, never allowing the character to settle into certainty.

Rami Malek’s contribution is subtle yet deeply affecting. His character reflects the lingering trauma left in the wake of genocide—those who must bear witness without fully healing. Malek’s restrained vulnerability becomes a haunting reminder that trials may end, but psychological wounds do not.

John Slattery rounds out the ensemble with sharp precision, portraying ambition and pragmatism as ever-present forces within the courtroom. His performance highlights how personal legacy and political calculation can quietly influence decisions that claim to be purely moral.

The screenplay is unflinchingly intelligent. Dialogue-driven and deliberately paced, the film trusts its audience to engage with complex ideas rather than emotional manipulation. Arguments unfold like chess matches, where every move carries legal consequence and ethical weight.

Visually, Nuremberg embraces stark realism. Muted palettes, rigid compositions, and oppressive interiors reinforce the gravity of the proceedings. The absence of stylistic excess allows the performances and ideas to dominate, creating an atmosphere of relentless seriousness.

What makes the film truly powerful is its refusal to offer easy answers. Nuremberg does not suggest that justice can undo atrocity, nor does it pretend that verdicts heal nations. Instead, it asks whether law can meaningfully respond to crimes that shattered the very concept of humanity.

The emotional impact builds quietly but persistently. As evidence mounts and testimonies unfold, the audience is forced into the same uncomfortable position as the judges and prosecutors—witnesses to horror, tasked with deciding how history should respond. The discomfort is intentional, and necessary.

In the end, Nuremberg (2025) stands as a sober, essential work of historical cinema. It is gripping without sensationalism, morally complex without indulgence, and deeply human without sentimentality. The film reminds us that justice is not measured by comfort or certainty—but by the courage to confront the truth, no matter how unbearable it may be.