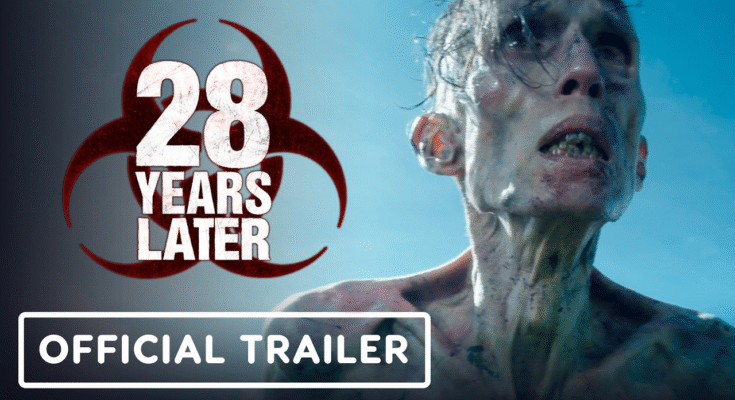

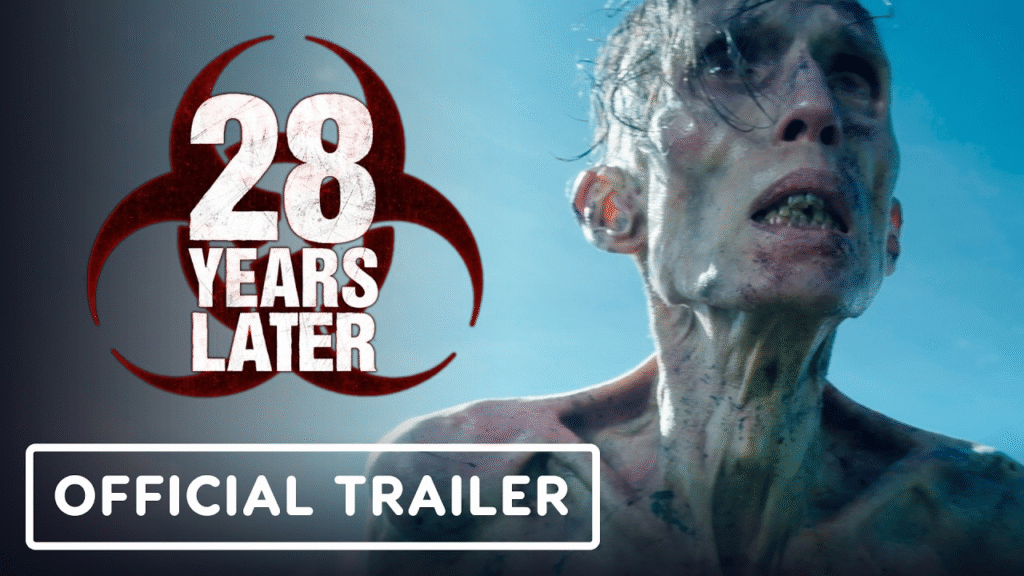

28 Years Later (2025) crashes into cinemas as a ferocious, breathtaking revival of one of the most influential horror sagas in modern film. Directed by Danny Boyle and written once again by Alex Garland, the long-awaited sequel transforms apocalypse into poetry — a searing vision of survival, guilt, and evolution. This is not merely a return to infection and chaos; it is a haunting meditation on what remains when rage becomes the only thing that still feels human.

The film opens nearly three decades after the original outbreak that decimated Britain. What’s left of the world exists in fractured colonies — fenced, patrolled, and ruled by fear. Humanity has adapted to containment, not freedom. But when an unmarked vessel drifts ashore on the Irish coast, carrying a single infected survivor frozen in cryostasis, the nightmare begins again. This time, the Rage Virus has mutated — slower to spread, but impossible to contain.

Cillian Murphy returns as Jim, the reluctant survivor whose body has healed but whose soul never has. Haunted by what he’s seen and done, Jim lives alone in the ruins of Dublin — a ghost of a man watching civilization rebuild itself around lies. His quiet life shatters when he meets Nia (Florence Pugh), a young medic from the European Federation tasked with securing the frozen carrier before it’s weaponized. But as new infections erupt and communication collapses, Jim realizes the world didn’t survive — it simply forgot.

Boyle’s direction is electric, visceral, and unflinching. Shot with his trademark handheld realism and feverish editing, every frame feels alive with danger. He captures apocalypse not as spectacle but as texture — the sweat on a trembling hand, the reflection of fire in a survivor’s eye, the pulse beneath the silence. The world of 28 Years Later feels too real, too close, as if civilization itself is an infection that never fully healed.

Cillian Murphy delivers a devastating performance. His Jim is older, hollow, but still capable of ferocity. He carries the weight of every death from the first two films, and Murphy plays him with quiet despair that bursts into frightening intensity when survival demands it. Florence Pugh’s Nia is the perfect counterpoint — hopeful, furious, and morally grounded. Their chemistry is not romantic, but human — two souls clinging to decency in a world where it’s a liability.

The supporting cast adds depth and tragedy. Barry Keoghan plays Oren, a young soldier indoctrinated into a militarized “sanctuary” that harvests infected blood for research. His arc — from loyal soldier to horrified witness — mirrors the film’s thesis: that control is just another form of infection. Naomie Harris returns briefly as Selena, now hardened into myth. Her presence — quiet, fierce, fleeting — reminds us of the cost of survival across generations.

Visually, 28 Years Later is both haunting and hypnotic. Cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle returns with a palette of decay and light — fog-choked ruins, abandoned ships glowing with crimson, and rural fields crawling with infected that move like shadows in wind. The imagery feels painterly, yet raw — every scene drenched in unease. When the virus reaches mainland Europe, cities ignite in slow motion — not explosions, but implosions of light and humanity.

The soundscape is pure dread. Silence hums louder than screams, broken by sudden bursts of chaos. Composer John Murphy reprises his legendary “In the House – In a Heartbeat” motif, reimagined with orchestral sorrow. The score grows like infection — subtle, rhythmic, consuming — until it swells into operatic despair.

Thematically, 28 Years Later (2025) examines cycles — how history repeats when humanity refuses to change. The virus, now spread through emotion rather than blood, becomes a metaphor for inherited rage — for the trauma passed from generation to generation. Boyle and Garland ask the hardest question: if rage defines survival, what does peace even mean?

The final act is pure cinematic devastation. As Jim, Nia, and Oren attempt to destroy the facility that created the new strain, the infected swarm like a storm reborn. Jim sacrifices himself to flood the compound, choosing oblivion over another cycle of control. In his final moment, he sees the sunrise through shattered glass — red, beautiful, and merciless.

The last scene is quiet, ambiguous, unforgettable. Nia stands alone on a hill overlooking the burning city. The camera pulls back, revealing fields of wind turbines — clean, sterile, lifeless. For a moment, she smiles — until one of the turbines slows… and stops. The infection has learned patience.

28 Years Later (2025) is a masterwork — furious, mournful, and breathtakingly alive. Danny Boyle delivers not just horror, but truth: that rage is never defeated, only buried beneath fragile peace. It’s the most human apocalypse ever filmed — one where the monsters are our own reflection.

The world didn’t end.

It adapted. 🔥