When Gina Prince-Bythewood’s The Woman King premiered in 2022, it felt less like a movie and more like a reclamation — a thunderous epic that carved space for stories too often erased from cinematic history. Both intimate and sweeping, the film tells of warriors, mothers, and leaders who fought not just for survival, but for the soul of a nation.

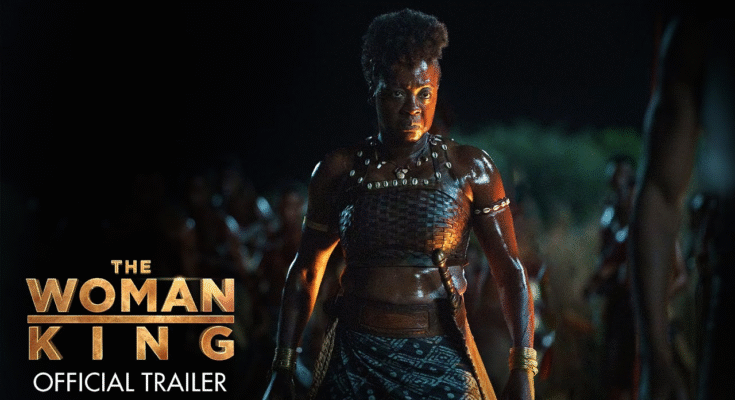

Set in the Kingdom of Dahomey in the early 19th century, the story centers on the Agojie — an all-female army whose skill, ferocity, and discipline made them legendary. Viola Davis anchors the film as General Nanisca, a woman of steel and scars, haunted by past traumas yet unyielding in her devotion to her people. Her performance is towering: every glance carries authority, every battle cry reverberates with centuries of rage and resilience.

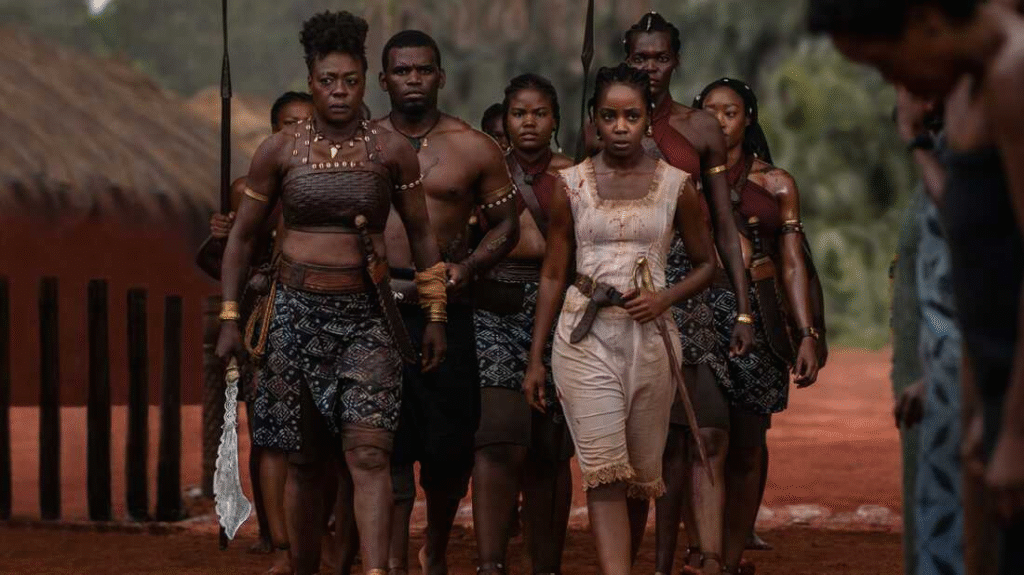

The plot intertwines warfare with personal reckoning. Nanisca trains the next generation of warriors, including Nawi (Thuso Mbedu), a spirited young recruit whose defiance mirrors her own youth. Their bond — at once maternal, combative, and tender — forms the emotional spine of the film, elevating it beyond battlefield spectacle into something deeply human.

Visually, The Woman King is breathtaking. The cinematography captures both the lush beauty of West Africa and the brutality of war. Golden sunrises over fields of training warriors, sweeping shots of fortified cities, and intimate candlelit rituals immerse viewers in a world rarely given space on the big screen. The action is choreographed with precision and ferocity — balletic yet brutal, every strike carrying weight and consequence.

The film does not shy from complexity. It confronts Dahomey’s entanglement in the slave trade, refusing to paint history in absolutes. Instead, it wrestles with the contradictions of power, survival, and morality, giving the story both grit and nuance.

The supporting cast shines. Lashana Lynch as the fierce yet wry Izogie delivers both humor and heartbreak, while Sheila Atim as Amenza provides spiritual grounding. Together, the ensemble creates a tapestry of strength, vulnerability, and sisterhood.

Terence Blanchard’s score elevates the film to myth. Drums thunder with urgency, choral voices rise with defiance, and quiet strings linger in moments of intimacy. The music pulses with both ancestral memory and cinematic grandeur.

The climax is both harrowing and triumphant. Battles are fought not only with steel but with choices — choices that redefine loyalty, family, and freedom. By the end, victory feels less about conquest and more about reclamation: of self, of voice, of identity.

The Woman King succeeds because it redefines what a historical epic can be. It is not a tale told through colonial eyes, but through the gaze of those who lived, bled, and ruled. It is a love letter to courage, resilience, and the unbreakable bonds of sisterhood.

In the end, the film is both celebration and challenge — a reminder that history is vast, that heroes wear many faces, and that stories once silenced can roar louder than ever when finally given the stage.