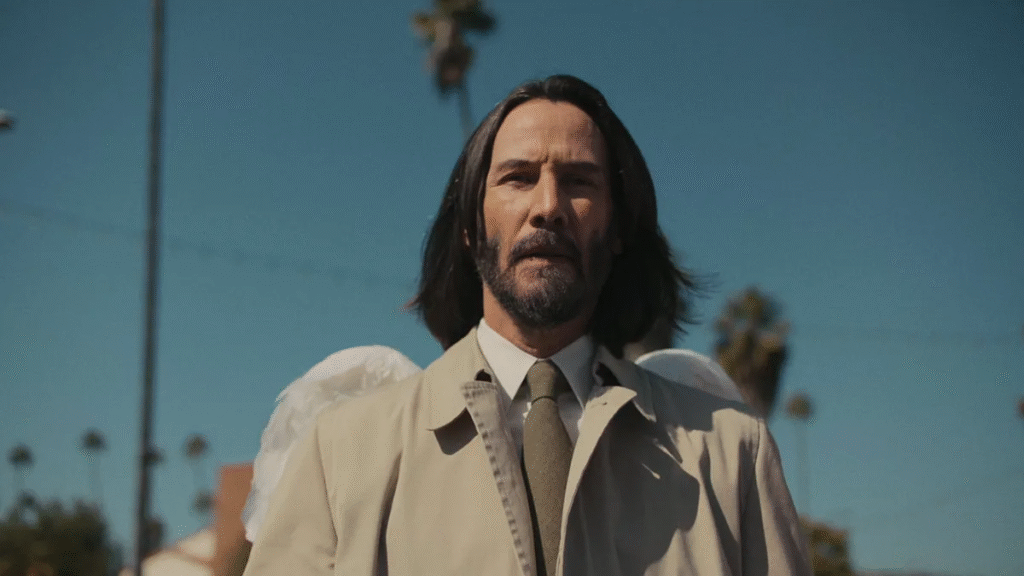

“I fell once. This time, I rise on my own terms.” With that whispered defiance, Heavenfall: The Last Seraphim declares itself not just as a dark fantasy epic—but as a celestial tragedy of immense scale and staggering intimacy. In a world where gods no longer answer and angels fall like ash, director Alex Proyas (The Crow, Dark City) delivers a gothic masterwork pulsing with rage, beauty, and the broken echoes of belief.

At its heart stands Keanu Reeves as Azrael—once the fiercest of the Seraphim, now an angel cast out for refusing to execute an order that would have scorched a world to ash. This isn’t the angel of light we’ve seen in storybooks. Reeves’ Azrael is weary, hollow-eyed, and haunted—wielding a flaming blade not with righteousness, but with the fury of a soul that has seen too much, lost too much, and still stands because something—anything—has to.

Azrael wanders the mortal world like a myth left to rot. He saves where he can. Punishes where he must. And always, always watches the sky for the home that no longer welcomes him. Reeves brings to the role his signature stoicism—but underneath it, a deep ache. Every silence speaks volumes. Every swing of the blade is a question without an answer.

The plot ignites when a rupture tears open the veil between realms. The Abyss is no longer just a whisper in prophecy—it’s here. It bleeds into the world through dreams, corrupted skies, and shattered sanctuaries. Demonic legions, not of flame but of void and echo, rise under the command of a fallen archangel known only as The Covenant, played with chilling grace by Mads Mikkelsen. He doesn’t scream—he tempts, with truths twisted just enough to become poison.

Sophia Lillis shines as Liora, a young oracle marked by celestial fire, destined to either reignite Heaven’s flame—or extinguish it forever. Her bond with Azrael forms the emotional spine of the film: a surrogate daughter pulling hope from a father figure who’s nearly forgotten the word. Their scenes are soft embers in a world gone cold, offering something rare in high fantasy—grace without grandeur.

Eva Green delivers another magnetic turn as Samael’s twin, Seraphina, the last angel allowed to walk both Heaven and Earth. Torn between loyalty and doubt, she becomes Azrael’s mirror—what he could have become if he’d compromised. Their confrontation—part duel, part confession—is one of the most emotionally charged moments of the year.

The cinematography is pure visual poetry. Heaven is not gold and clouds—it’s alabaster ruins and fractured stars. Earth is painted in shadow and stormlight, while the Abyss crackles with inverted fire and impossible geometry. Proyas crafts every frame like a painting, echoing Caravaggio and Giger in equal measure.

The action, when it erupts, is brutal and balletic. Blades of light clash with spears forged in void. Wings tear through reality. Time bends. Faith breaks. And amidst the carnage, Azrael moves like a specter—less warrior, more reckoning.

But it’s the philosophy beneath the spectacle that elevates Heavenfall. This isn’t a tale of good vs. evil. It’s about disillusionment. About angels who once believed and now simply endure. About a war where no one remembers why it began, only that it can’t end. The film asks: What does redemption mean in a system built to break you? And can salvation come not from forgiveness—but from defiance?

By its devastating final act, where Azrael must choose between restoring what was or forging something new from the ashes, Heavenfall transcends genre. It becomes myth. Not one of triumph, but of refusal. Of a being who fell not for sin—but for mercy.

🔥 Heavenfall: The Last Seraphim is not light fantasy—it’s a requiem. And in its darkest moments, it offers the most radiant truth: sometimes, the fallen don’t need saving. They need to rise on their own terms.