Some apocalypse films roar with chaos. Zombie War 2 (2026) begins with silence — the kind that hums inside your bones long after the world has ended. This is not a story of the undead rising; it’s a story of humanity collapsing — and what remains when the noise dies down.

Andrew Lincoln returns to the wasteland like he never left it, carrying the ghost of every leader he’s ever played. His unnamed commander is not a hero — he’s a man eroded by decisions, by survival itself. Each line on his face feels carved by the cost of leadership in a world where every order leaves another grave behind. Lincoln’s performance is a quiet revelation — weary, restrained, and brutally human.

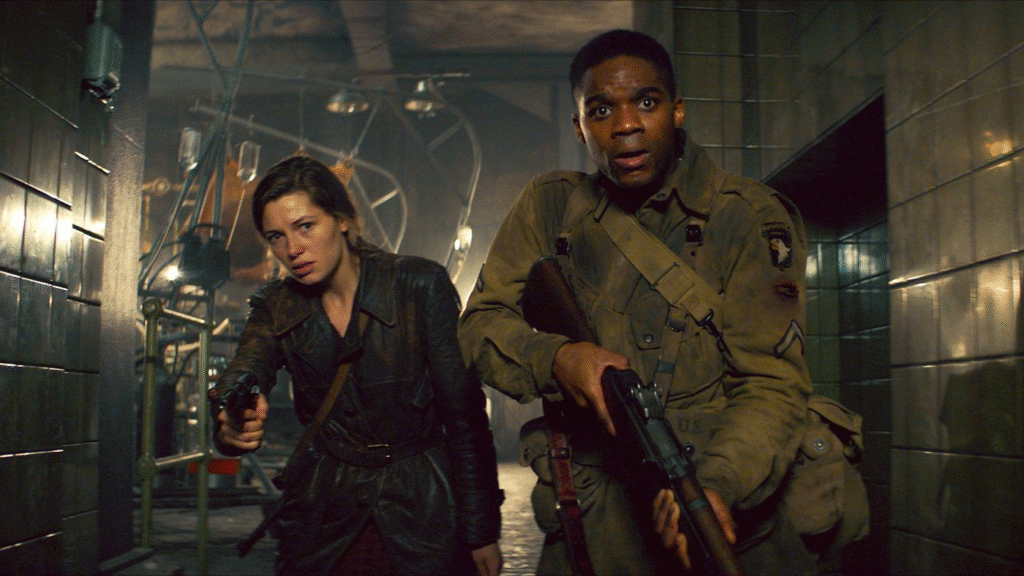

Opposite him, Milla Jovovich reignites her action legacy with feral grace. Her character, a former soldier turned mercenary of solitude, is both blade and wound — every move precise, every glance hiding a storm. Jovovich strips away the genre’s clichés, replacing gunfire with guilt, speed with silence. She trusts no one — and the film never lets you forget why.

And then there’s Norman Reedus, the soul of the film’s desolation. He speaks less, but his presence says everything. A scavenger, a survivor, a man still trying to remember what hope used to feel like. Reedus moves through the ruins like a ghost refusing to rest, and when he finally speaks of wanting “one more sunrise,” it feels less like dialogue and more like a prayer.

Directed with chilling restraint by David Fincher, Zombie War rejects the spectacle of apocalypse for something colder, sharper, and infinitely more personal. There are no heroes, no sanctuaries, no miracles — only human beings trying to stay human in a world that no longer recognizes the word. The zombies here are almost peripheral — shadows, metaphors, mirrors. The true horror lies in the survivors’ eyes.

The cinematography is stunning in its despair. Entire cities lie drowned in ash-gray light; forests stretch silent, unbreathing, littered with remnants of the world we once knew — a child’s shoe, a torn flag, a plane half-buried in the mud. The camera lingers not on violence, but on aftermaths — the quiet horror of what remains after the screams.

Fincher’s meticulous pacing transforms the film into a meditation on endurance. Every frame feels like a test of will — how long can we hold on when everything worth holding is gone? The violence, when it comes, is sudden and unromantic, more survival than spectacle. Yet within that brutality lies an aching tenderness — a flicker of compassion that refuses to die, even when everything else has.

The score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross hums like the world’s final heartbeat — industrial, distant, and painfully human. It doesn’t lead the scenes; it haunts them. The music bleeds into the static of broken radios, into the rhythm of boots on concrete, until the line between sound and silence disappears completely.

What makes Zombie War unforgettable isn’t its horror — it’s its honesty. It asks the question most apocalypse films avoid: what if survival isn’t the reward, but the punishment? Every character here is fighting ghosts — of who they were, what they lost, and what it means to keep moving when there’s nowhere left to go.

And then comes the final scene: dawn breaking over a shattered horizon, smoke drifting like memory, and a single voice over a dying radio — “We’re not fighting the dead. We’re fighting the memory of what we used to be.” It’s not just a line — it’s the film’s entire heartbeat, distilled into one truth too heavy to carry.

Zombie War (2025) is not about saving the world. It’s about accepting that it’s gone — and still finding the courage to walk through the ruins. A haunting, elegiac masterpiece that redefines the apocalypse not as destruction, but as reflection.

When the sky falls and the dead rise, it’s not the end of the world. It’s the beginning of remembering what it meant to be alive.