There are horrors born of darkness, and there are horrors born of love. The Unborn Curse (2025) dares to explore both, weaving a nightmare that begins with the most sacred of miracles—a pregnancy—and ends with a revelation that turns creation itself into a haunting act of doom.

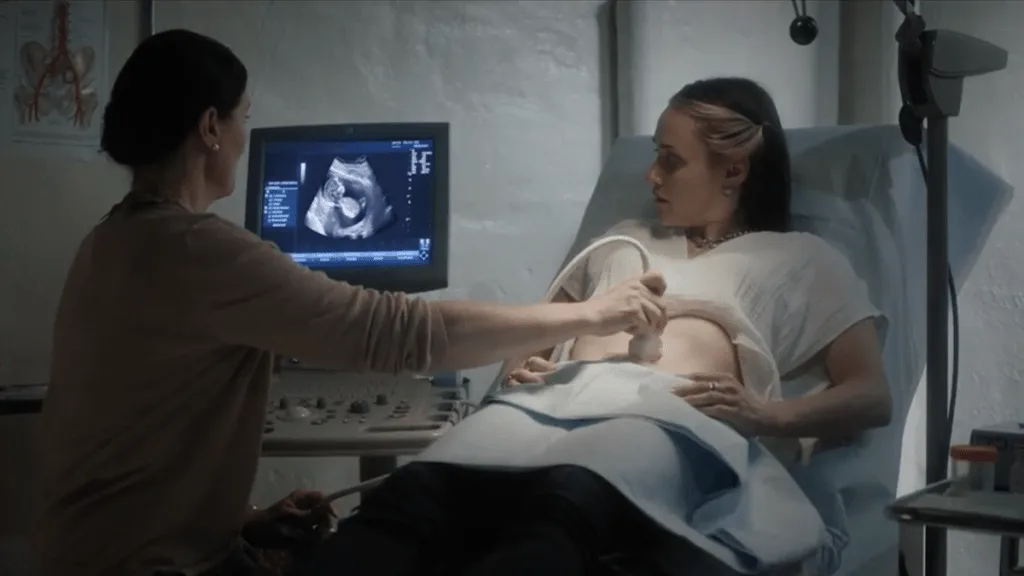

The film opens in silence. A young couple receives the news they’ve long prayed for: they’re going to be parents. The glow of joy is palpable, the world around them seems gentler, lighter. But as the months pass, that light begins to fade. The mother, played with haunting fragility by Florence Pugh, begins to feel movements that are not quite human, hear whispers when no one is near. The miracle they once celebrated soon becomes an unholy visitation.

Director Ari Aster crafts each scene like a waking nightmare, blending body horror with psychological torment. The slow pacing forces the audience to breathe in the dread—to live inside the characters’ fear rather than merely witness it. The horror doesn’t lunge; it seeps. It grows, like something alive and watching beneath the skin.

The father, portrayed by Oscar Isaac, grounds the film with a performance of desperate devotion. His transformation—from rational protector to trembling believer—is the emotional backbone of the story. As he digs deeper into the mystery surrounding their unborn child, the film’s religious and mythological undercurrents rise to the surface: ancient symbols, forgotten rituals, and the suggestion that their child’s conception was no accident, but fulfillment of an ancient curse.

Visually, the film is a masterpiece of dread. The color palette shifts from warm amber to pallid gray as the pregnancy advances, mirroring the decay of hope. Hallways stretch too long, mirrors reflect things that shouldn’t be there, and every shadow feels sentient. Cinematographer Greta Zozula captures the claustrophobia of domestic life collapsing under supernatural weight.

Sound plays a devastating role. The whisper of the unborn becomes the film’s most chilling motif—soft, rhythmic, almost tender, until it isn’t. In several sequences, the sound design alone is enough to make the audience recoil, as if the womb itself were speaking.

But The Unborn Curse is not horror for horror’s sake. Beneath the demonic possession and the occult terror lies a deeper tragedy: the fear of motherhood itself. The film exposes the fragile boundary between creation and destruction, between the sacred and the profane. The mother’s body becomes both cradle and battlefield—a vessel where love and evil wage their quiet, merciless war.

What truly elevates the film is its refusal to explain everything. The ancient pact that fuels the curse remains half-seen, half-whispered. We are left uncertain whether the evil is divine punishment, human sin, or the ultimate irony of existence—that life itself might be the cruelest curse of all.

The performances are intimate and shattering. Pugh delivers terror that feels almost maternal—her fear isn’t of dying, but of bringing something monstrous into the world. Isaac’s anguish mirrors hers, turning devotion into obsession. Their chemistry—two souls collapsing under the same nightmare—makes every scream and every silence heartbreakingly real.

In its final act, the film descends into pure mythology. Blood, faith, and sacrifice merge in imagery both horrifying and transcendent. The ending doesn’t offer closure; it offers revelation—a reminder that some horrors are not meant to be stopped, only understood.

The Unborn Curse (2025) lingers long after the credits fade. It is a film that dares to ask what happens when creation turns against its creator—when the miracle of life becomes a message from the abyss. Unflinching, poetic, and devastating, it stands as one of the most haunting explorations of faith, fear, and the limits of love in modern horror cinema.